The word “decline” sounds heavy and oppressive. It generally carries a negative meaning and refers to decreased quality of life, contraction, disappearance. The expression “managed decline”, though not new, starts from the idea that decline in certain areas—be it geographic or sectoral—is inevitable. Certain political ideologies, such as the degrowth movement, even view this organized decline as useful, part of an effort to shrink the economy in order to save the environment. These ideologies challenge the idea of perpetual growth and propose an economic model where reduced consumption, emissions, and resource use is a deliberate choice.

But while these movements remain relatively marginal, decline caused by social or contextual changes is quite common. In developed societies that have passed through rapid industrialization, urbanization and the demographic transition, signs of stagnation or even contraction are appearing across multiple fronts—be it agriculture, traditional heavy industry or the existence of viable rural communities. Decline is not just a statistical variable; it is a lived reality: falling student numbers in schools, village shops closing down, trades disappearing, reduced public transport—these are all symptoms.

Managing this decline is not a passive process but one that requires choices: how do you redistribute resources? What do you abandon and what do you preserve? What do you symbolically retain for the community’s sake, and what do you sacrifice for efficiency? Unfortunately, these decisions are often influenced by complex local political interests. In certain cases, these interests prevail to the point where public money ends up funding various “white elephants” in regions that do not truly need them.

Decline as a function of demographics

At Rethink, we’ve discussed various facets of decline, but the most frequent topic has been demographic decline. Population shrinkage and aging are already prevalent in Europe and East Asia, and appear to be becoming a dominant global trend (with exceptions such as Africa, Central Asia, and countries like Israel, Iraq, or Pakistan). As we’ve seen in our earlier articles, population decline leads to young and active people concentration into a small number of dynamic metro areas, contributing to a rise in regional disparities.

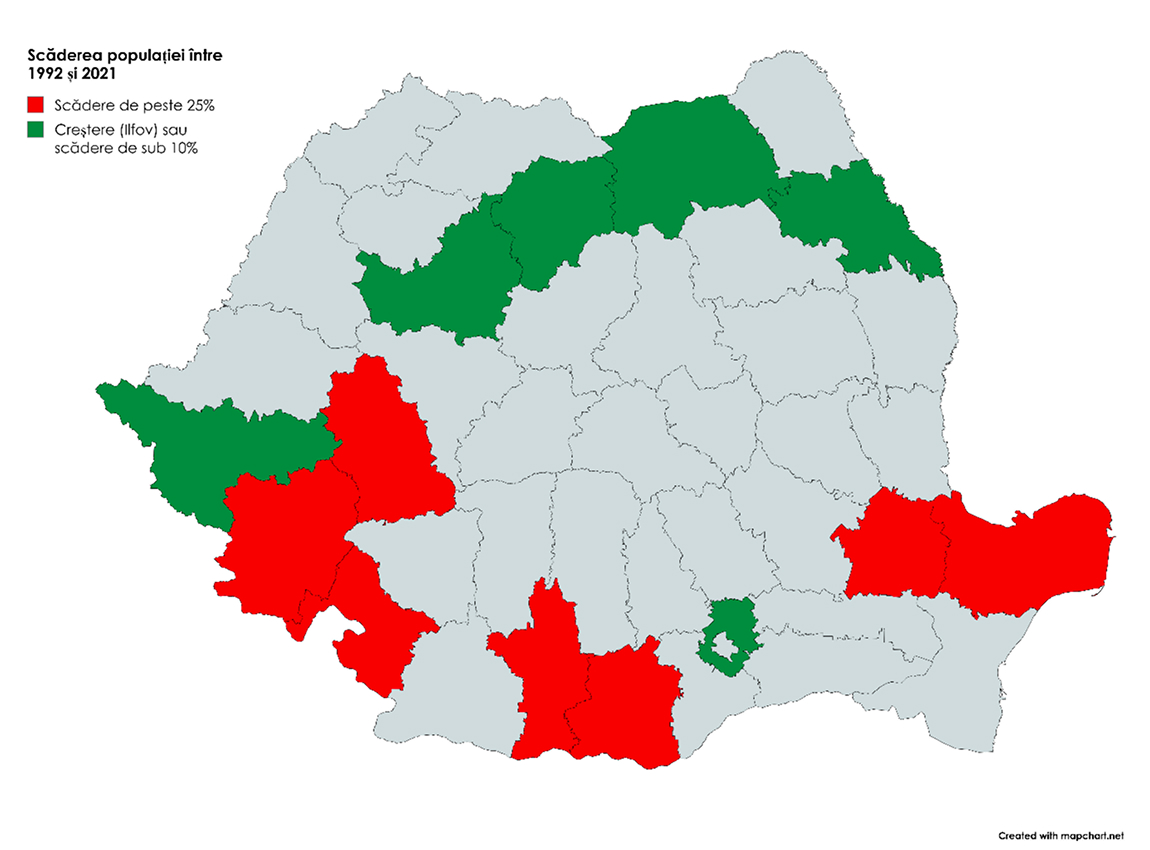

In Romania, accelerated demographic decline is already present in several counties. In Olt, Brăila, Tulcea, Mehedinți, Teleorman, Hunedoara, and Caraș-Severin, the population decreased by more than 25% between 1992 and 2021. The downward trend will most likely continue, driven by an already lopsided population pyramid.

In these counties, decisions will need to be made regarding the restructuring of public services, road and rail networks, and perhaps even the organized abandonment of certain villages. In isolated cases, quality local administration and investment can reverse local negative trends, but this remains rare. For example, although Hunedoara County is well-connected to the highway network and a recently upgraded rail corridor, its population decline has continued in recent years. Similarly, countries like Spain have had a comparable experience: the northern part of Castile, despite massive infrastructure investment, did not benefit from sustainable revitalization. In the context of demographic decline, infrastructure cannot adequately compensate for the loss of human capital. An attractive university and startup scene is a better form of “infrastructure” than a motorway.

In the case of Romania, investments should be reprioritized in favor of counties that are relatively demographically resilient. This would facilitate economic development in areas where there is sufficient human capital to generate local demand and supply for goods and services, as well as secure conditions for future growth. A good example of a useful investment would be the creation of an east-west transport corridor in the northern part of the country. Or the concentration of spacious housing construction around major university centers.

The political costs

Even though solutions to regional demographic decline seem relatively intuitive, their implementation runs into political calculations and social costs. Locals often resist; in some countries, political movements have emerged specifically to prevent any reduction in the supply of public and private services. In the isolated area of southern Aragon (Spain), a political force called “Teruel exists!” emerged—a party devoted to opposing any attempt by the state to “withdraw” from the province.

When policies enacting managed decline are enacted, political struggles often ensue. For authorities, decisions should be simple—adapting public services to the new demographic reality in order to keep them afloat. In other words: closures, layoffs, mergers. Sometimes these are driven by financial reasoning (the cost per beneficiary becomes very high and funding comes mainly from outside the region), other times by a simple lack of human resources: too few doctors or teachers are willing to settle in rural, poor, or opportunity-scarce areas. In practice, we get either adaptation by decision or natural downsizing.

But at the local level, opposition tends to arise regardless of the source of the problem. People in Teruel will blame the government, but their collective behaviour (e.g. low fertility) contributed to the dismal demographics of the province. When the number of students in Romania dropped by 50% after 2008, uiniversities were encouraged to merge. Yet only a few (e.g., Eftimie Murgu University in Reșița and the North University in Baia Mare) took this step. In many other cases, local political lobbying led to the preservation of a relatively intact network of institutions, even though their service usage dropped significantly.

Elsewhere, efforts to rationalize public systems also tend to be difficult (or outright fail) due to the opposition of local political interests. In Germany, plans to close small rural hospitals face massive public opposition, despite evidence regarding the safety and efficiency of consolidated medical centers. Similarly, closing underused schools, merging municipalities, and other efforts to adapt administrative realities to new demographic contexts tend to fail in many European states. The pattern is the same: a difficult decision is followed by letters, protests, pressure from local MPs. Sometimes, the protests are justified—a hospital that is too far away may reduce the chances of surviving a heart attack, for example. But systemically, failure to adapt public services leads to lower quality for most beneficiaries.

Perhaps the most severe form of non-adaptation to real community decline is infrastructure-itis: the belief that natural decline can be fixed through infrastructure investment. Often, these ideas lead to the appearance of “white elephants”—costly and economically unviable projects. After long decades of population and economic growth, it is difficult to accept that a new investment or construction could be, somehow, bad. For example, a statement like “not every county needs a highway” would trigger widespread criticism in Romanian public discourse. That’s because political and social instincts were shaped in a different era, one where a concert hall might be a “white elephant,” but a road or airport would never be seen as such.

White Elephants

White elephants have been often covered in the media. For example, Spain was frequently mentioned for its many oversized projects, often built with European funds. The country now has a multitude of highways that will never recover their construction costs, underutilized high-speed railways, or airports with next to no flights. For example, a huge airport built near Ciudad Real is now abandoned. The city of Huesca, with only 54,000 inhabitants, got its own dedicated high-speed rail line. In 2017, it was used by a little over 100 passengers per day, with virtually zero chance of recouping the investment. Spain’s white elephants are influenced by political inertia, with national and regional leaders always viewing infrastructure investment (often at the expense of human capital) as essential. Prestige is often a major driver of white elephants. A good example is the Olympic stadium in Athens, used for the 2004 Games and then abandoned.

Tulcea Airport is a good example of a Romanian white elephant.

White elephants often appear when realities no longer align with the narrative of state or regional development, yet the narrative continues to dominate decision-making.

Examples exist in Romania as well. Recently, Tulcea Airport has been in the spotlight—a modernized airport serving a county with fewer than 200,000 inhabitants. In fact, Romania has more airports than Poland, despite having less than half the total air traffic and a more compact territory. A frequent host to white elephants is sports infrastructure: cities with urgent needs for basic infrastructure tend to invest in oversized stadiums and sports halls. In contrast, the preference for new projects over maintenance of existing infrastructure leads to the degradation of past investments. A good example here is the railway network in countries such as Romania or the former Yugoslavia.

In Romania, the availability of EU and national development funds risks perpetuating this tendency: in the absence of a clear national strategy to prioritize viable regions, an approach is adopted that is “equitable” on paper but inefficient in reality. As a result, investments continue in areas where demographic decline makes break-even impossible—schools without children, clinics without doctors, roads with too little traffic, new train stations served by degraded tracks.

Public investment comes with many hidden costs not obvious when the ribbon is being cut. They are often funded through loans, leaving interest burdens for future generations. They don’t come with maintenance budgets, which often gives them a short functional lifespan or limits the flexibility of local budgets. Unfortunately, some of these costs become evident only after the projects are completed.

AI and Managing Decline in the Labor Market

We’ve talked about infrastructure and white elephants, but perhaps the most important challenge in managing decline is handling the labor market. Across almost all of Europe—including Romania—the number of retirees is higher than the number of people entering the working-age population. For this reason, most governments and companies are seeking compensatory solutions—through immigration, retraining, raising the retirement age, or increasing worker productivity.

Technically, as AI technologies promise increased productivity, they could compensate for the shrinking working-age population, reducing the pressure to raise the retirement age to unreasonable levels. But this scenario requires a capacity for rapid adaptation and a rethinking of the human role in the economy. Many of those who remain active will need to become “technology managers” rather than “executors” of repetitive tasks.

A key problem is the difficulty of coordinating the labor market at a macro level in a free and flexible economy. Access to information about opportunities, retraining needs, and matching of individuals with the best employment options is still fragmented and difficult to fine tune into a comprehensive system that safeguards both the individual need for job security and meaning and the societal need to ensure a working economy. The state can, of course, intervene—not as an employer, but as a provider of informational infrastructure and support for economic mobility. At a more grassroots level, universities and vocational schools can adopt a more flexible logic, better integrated into a highly dynamic labor market.

Conclusions

Decline (regional, economic, demographic or otherwise) is not just a statistical diagnosis, but a reality with deep social, economic, and political consequences. A responsible state cannot fight it through denial or illusions of universal development; it must accept that some regions will have smaller populations and economies, while others will grow. “Managed decline” does not mean resignation—it means the courage to lucidly plan a decent transition for all citizens, even where the economic future is limited.

Today’s choices—in planing, infrastructure development, education, and labor force policy—will influence Romanian society’s ability to manage this transition fairly. We cannot offset decline with optimistic narratives, but we can prevent it from becoming a source of injustice and resentment. That, ultimately, is what solid governance means in an era full of challenges.

In concrete terms, we need to have the ability to be honest about what we can afford to have and what we can’t. Because for every white elephant built in defiance of reality there are not only costs, but also missed opportunities.

Brief summary

- Against a backdrop of population decline in peripheral regions, the issue of withdrawing certain public or private services has emerged in several European countries.

- The political costs of withdrawing public services lead to deferred decisions and, in many cases, to increased public spending.

- Although balancing costs and the right to access is important, a declining population will have negative consequences for both society and the economy that cannot be easily avoided.

- Ignoring demographic and economic realities leads to the emergence of “white elephants”. These are projects that fail to make-break even while providing limited public utility.

- A similar phenomenon is taking place in the labor market, where the decline in the working-age population makes restructuring certain services imperative.

- Unfortunately, although the emergence of artificial intelligence presents opportunities, the labor market cannot be easily reorganized or centrally coordinated in a free economy.