2025 and 2026 appear to be turning points for Europe. Against a backdrop of growing isolation and relative marginalization in global dialogue – now conducted in the language of power – there are discussions about economic revitalization, rearmament, and strategic autonomy. Unfortunately, Europe’s capacity for autonomy is severely limited by demographic stagnation that has not been adequately addressed and for which, in any case, there are no easy solutions.

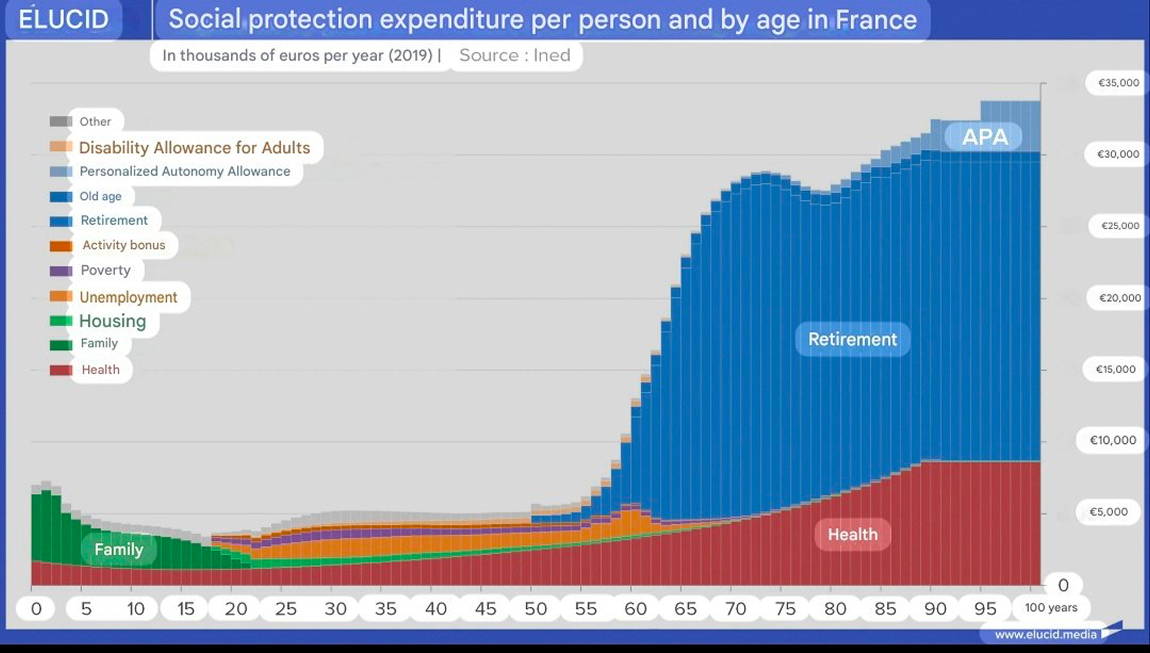

The European public sphere has nonetheless begun to notice the demographic elephant in the public finance room: pay-as-you-go pensions paid by current taxpayers for past generations (which are much more numerous). In no small part due to the legal protections that pension systems enjoy relative to other public expenditures, in many states these have come to rival or even exceed the average incomes of the active-age population. And the share of pensioners will most likely increase in the coming decades. In this context, Europe’s geopolitical ambitions risk coming into direct conflict with an increasingly difficult-to-sustain welfare state that is (especially in countries like Spain) lopsided towards the needs of the older half of the population.

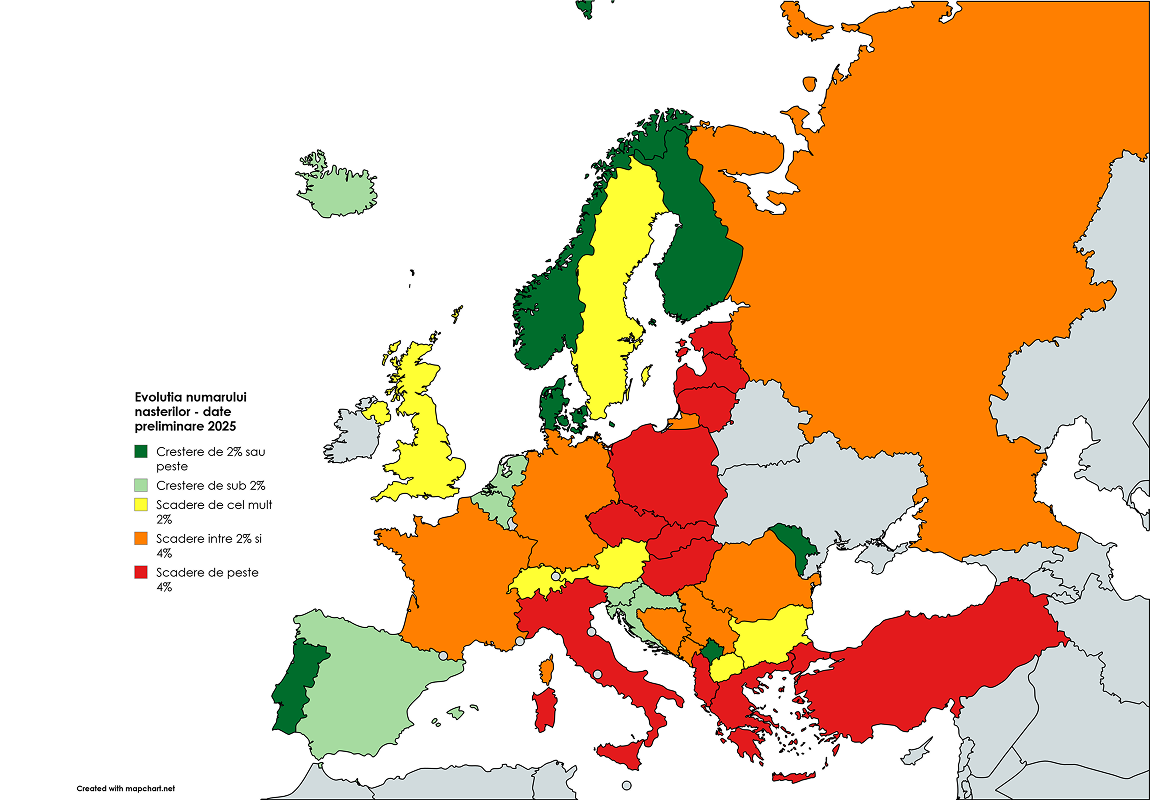

Figure 1 Year-on-year variation in births in European space. Source: BirthGauge X account, centralizing data from national statistical institutes. Only states with data for 9+ months included. Green states saw a rising numger of births, yellow a slight decline (0-2%), while red saw declines above 4% y-o-y.

The demographic crisis is not new. And we see it hitting the continent’s global prominence already. For example, Europe closed 2024 with a negative record regarding the number of births. Crucially, the bloc of 27 European Union states registered fewer newborns than the overall less populous United States of America, an aspect that will increase the chance of an American demographic sorpasso. In 2025, the gap between the US and EU27 will most likely widen, with preliminary figures indicating relative stability in births on the other side of the Atlantic amid ongoing European decline.

With the aging of the population, we observe an increase in the number of deaths across the continent. In 2024, their number exceeded that of births by well over 1,000,000. However, the difference was compensated by net immigration of over 2 million people. In the long term, though, the natural population decline will increase in absolute figures, and maintaining high net immigration faces the problem of political costs as well as difficulties in maintaining selectivity. Europe already has a very poor track record regarding integration, with many countries having large communities of people of immigrant origin who have low employment rates, a high level of dependence on social benefits, and whose children have poor school results.

The European Union is by no means the only region facing accelerated demographic decline. Russia, for example, will register in 2025 its 6th year in which the natural population decrease will be greater than 500,000 people. China had only 8 million births in 2025, over 2 times fewer children than its neighbours in India. Moreover, the population decreased by over 3 million people.

The situation at country level

When final data for 2025 is published, the number of births will most likely have increased in a small number of European states, among them Moldova, Kosovo, Portugal, Denmark, Finland, and Norway. A few other countries registered moderate increases in the number of newborns, with only Spain, the Netherlands, and Belgium among the largest (10 mil+ inhabitants) having a positive evolution.

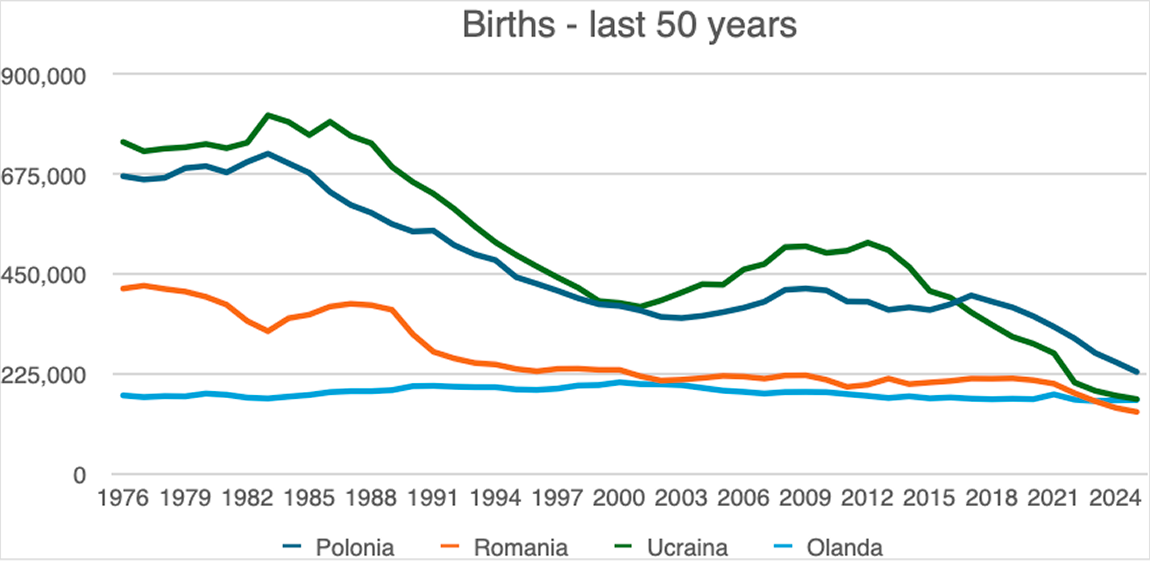

Several European countries now register twice as many deaths as births, notably the Baltic states Latvia and Lithuania. Russia is heading toward the lowest number of births since the 18th century. Poland, often cited as an example of a country “with a great future” in economic or other publications, has registered a veritable collapse in the number of births compared to the 1980s. In just 40 years, their total number has decreased by about 2/3. Poland is aging today at a faster pace than Japan or Italy, pioneers of the phenomenon, ever did.

Similarly, Ukraine now has a birth total comparable to Romania, against a backdrop of war and mass exodus. Yet in 1990, Ukraine had a population 2.3 times larger. This convergence reflects one of the most rapid population declines anywhere in the world. Moreover, the trend was profoundly negative even before the war began, despite the country’s Western regions having some of Europe’s highest TFRs. The situation is difficult to correct. Indeed, optimism about a postwar “baby boom” is likely to be misplaced. In the former Yugoslavia, for example, it was absent. Just as it was absent in Cyprus in the 1970s. There is no guarantee that the traditional postwar baby boom phenomenon is still a natural emanation of contemporary European culture.

A key trend for our region is the much more rapid decline of the child population in Central and Eastern Europe than in the rest of Europe. For example, Poland, Romania, or Ukraine have approached the annual number of births in the Netherlands, a country with far fewer children in the 1970s or 1980s. The share of births in Romania and Poland (the largest CEE states) in the total of the current European Union has decreased from 18.2% (1990) to 13.6% (2010) and 11.1% (in 2024).

Figure 2: Number of births in the last 50 years (for 2025, the forecast is based on preliminary data from reported months; for Ukraine, data includes current territory). Sources: CBS Netherlands, Eurostat, INS, GUS

European countries that have managed to temper the pace of declining birth rates have most often done so thanks to very high immigration. In many countries, over 1/3 of the total number of births is due to foreign born mothers. This has begun to generate rapid changes in population composition in much of Western Europe. For example, in England, less than 55% of births are registered as “white British,” an ethnic group that represented about 95% of the country’s population just 50 years ago. These figures have come to be used in public discourse to criticize the political centre, with this rhetoric now common in the right, far-right, and beyond. Several Nordic countries have begun to openly discuss the problem of immigrants’ contribution to the economy, which is very low in the case of people from the MENA region. At the same time, PISA tests highlight a picture of poor school integration of immigrant children every 3 years, sparking polemics and discussions but rarely measures with real impact. This portrait is all the more problematic as immigrant children in other states (especially English-speaking ones, but also in the Persian Gulf or Singapore) manage to have remarkable school results, often superior to those of non-immigrant children.

What are the implications for Europe?

The continuation and worsening of the demographic crisis will drastically limit the vitality of the European economy and the sustainability of the welfare state. At the same time, it will prevent European countries from allocating resources to unexpected challenges, such as rearmament efforts, support for local industrial champions, or stimulus measures during various crises. There simply will be no fiscal manoeuvring room.

Unfortunately, politicians on the now aptly named “old continent” have largely given up on actively tackling the problem due to problematic electoral arithmetic. As European populations age, the “grey” vote becomes increasingly powerful, and pension and health expenditures keep ever larger parts of the budget locked. Some countries, like Spain, have opted for more immigration to ensure an increase in the number of contributions to the social insurance system. Others, like the Netherlands, have introduced modern pension systems that are not completely dependent on current contributions. But very few European states have managed to successfully push for the two main demographic solutions to the crisis: increasing the number of births and better integration (or selection?) of immigrants. On the contrary, the birth rate continues to decline, and immigration is only slightly more selective than a decade ago.

Depopulation threatens the viability of public services or even countries

The crisis is still a structural-economic one in most of Europe, but certain states are already threatened with loss of viability. In 2025 we discussed the case of Latvia, a country facing simultaneously the decline in the number of inhabitants, the concentration of the remaining population in a single metropolitan area, and the fragility of the ethnic Latvian majority. Throughout 2025, Latvia’s demographic situation worsened even further, and many districts now have fewer than 10 inhabitants/km².

A grave (and more urgent) threat is not necessarily to the viability of states as sovereign political entities, but to their infrastructure of public services, transport, etc. As more regions depopulate, previous investments in roads, railways, hospitals, and schools will become sunken costs. Maintenance and personnel costs will require support from central budgets, support that will compete with more urgent matters and priority areas.

Technology as a saving solution?

There is the possibility of factors emerging that could ameliorate the impact of demographic decline, for example the augmentation of productivity with the help of artificial intelligence and other technologies. Or the increase in healthy life expectancy. But even here there are numerous obstacles when it comes to implementation. There is no coherent approach to taxing the “work” of artificial intelligence, a problematic aspect given that many European pension systems are tied directly to employee contributions. And the increase in life expectancy should be accompanied by “real time” adaptation of retirement age and norms.

Moreover, economic and technological transitions require both coordination and efforts to limit social impact. Given that the incomes of many Europeans have stagnated for years, the political cost of further declines in quality of life could be extreme.

Why should demographic challenges be central to european public policies?

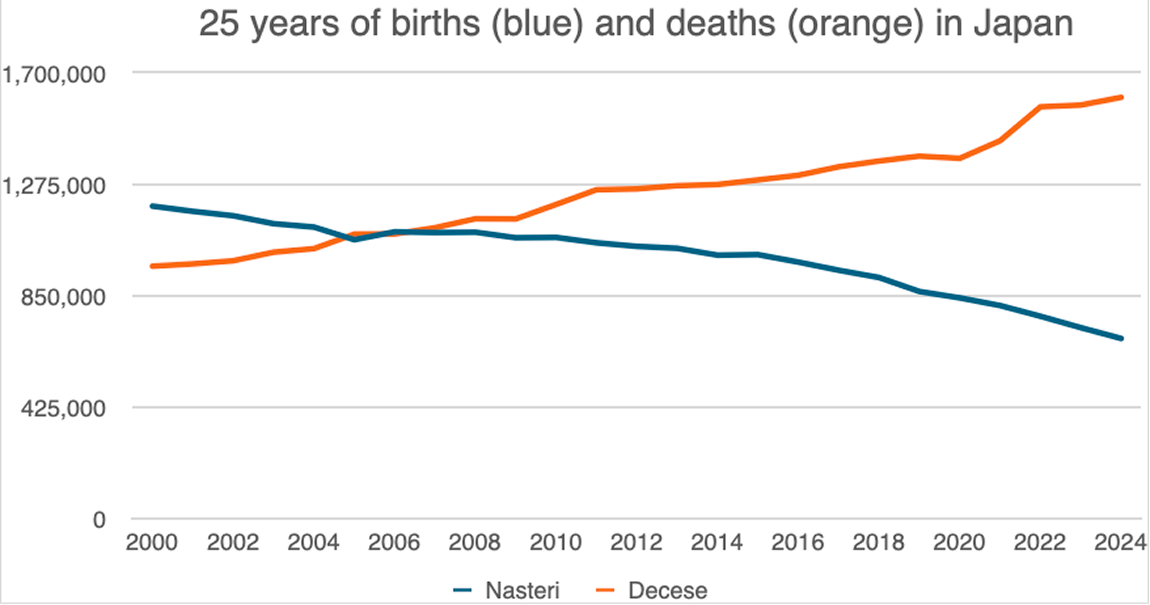

At Rethink, it is clear to us that Europe’s grand geopolitical and economic strategies will not succeed in taking shape as long as the continent ages and depopulates at speed. Although very few people internalize this, the population is declining in geometric progression. Once the natural population decrease begins, it is rapid in societies with low fertility. Japan is the classic example where the depopulation problem was ignored as long as demographic inertia maintained a stable trajectory. But just 20 years after the first natural population decline, we now see natural demographic contraction to the tune of 1,000,000 people per year.

Today, countries like Italy are in a similar position to Japan, with a slight “mask” provided by migration. Countries like Poland are on track to register an even more abrupt collapse, in the absence of a saving deus ex machina.

As with the climate crisis, the difficulty (or impossibility?) of solutions leads to public exhaustion and the redirection of the public agenda to other areas. Playing pretend is good for morale, even if a form of deferring the emotional costs of reality. Unfortunately, the demographic crisis will not disappear just because it is not present in the attention of political parties. And the indirect political costs (given mainly by deficits, lack of money, austerity) will not allow the political class to escape its consequences either. One can pay pensions, but not once the money dries up.

How could the demographic crisis be addressed?

All measures to address the demographic crisis have failed, with cases of occasional success (Georgia, Mongolia, and a few other states) being rather temporary. In Europe, the subject is also intensely politicized: the idea of explicit pro-natalist measures irritates the left, while solutions centered on migration are increasingly criticized by part of the political right. Dogmatic attitudes to tackling the crisis make it less likely for policies to have a real impact.

On the other hand, despite a sense that the problem cannot be tackled with money, resources directed toward combating the demographic crisis have often been modest – in almost all European countries, aid for families is a fraction of that oriented toward pension payments. Even in states with generous family support schemes, young parents receive much less money than pensioners. In fact, the entire architecture of social systems is anachronistic, not being designed for an era in which families have an important role in economic continuity and state sustainability. In contrast, pay-as-you-go pension systems are designed for another historical era. One with many children but very few people who enjoyed their legal retirement for years and decades.

Figure 3: Social spending distributed by age. Source: Euclid Media with translation by Francois Valentin (X account)

But there are a few steps that Europe can take urgently to start more adequately addressing what is likely the continent’s most pressing crisis. A first urgent, necessary measure would be recognition of the demographic crisis as a fundamental threat to Europe and prioritizing it in public policy. Any strategy, development plan, or national vision should realistically take into account the demographic situation, the data describing its causes, or measuring the effectiveness of measures already attempted. Including in relation to other policy areas. Want to make those houses more energy efficient? Not if it makes them more expensive for first-time buyers.

Second, there is a need for a profound rethinking of the social contract between generations. Investments in families and children must become a budget priority comparable to pension expenditures. It must be publicly recognized (and explicitly communicated to Europeans) that without a stable demographic base, the entire social protection system becomes unsustainable. Early, special, or significantly above-average-salary state pensions must be eliminated. For families, more generous allowances are not enough – integrated policies are needed that address the real costs of raising children: affordable housing, reasonably priced childcare, workplace flexibility, and elimination of professional penalties for parents (these are generally illegal, but continue to exist in practice).

Third, public dialogue about demography must be depoliticized and anchored in reality. As long as the debate remains blocked between ideological camps, pragmatic solutions will be impossible. European societies must accept that neither pro-natalist measures alone, nor migration alone will solve the crisis, but only a balanced combination, adapted to each country’s context, can mitigate the impact.

Fourth, addressing the demographic crisis must be unchained from institutional constraints and the customs of traditional public policy. Funds must be allocated directly toward combating the problem. For example, it would be absurd for countries where the demographic situation is critical (like Latvia) not to be able to benefit from dedicated European funds to combat population decline but to be able to access them to build uneconomic infrastructure precisely because of the lack of users.

Fifth, a wider societal dialogue needs to exist on the wider, cultural forces that are fuelling the demographic crisis. There is growing evidence that the world-wide decline in fertility rates seen in the past decade is at least partially fuelled by falling rates of couple formation. This, in turn, seems to be to some degree a byproduct of a new global culture shaped by social media.

And lastly, we need to remember that the demographic crisis is not a fatality that must be passively accepted, but neither is it a trend we can combat with simple solutions. It is the result of profound structural transformations in how we live, work, and organize our societies. The response must be commensurate: ambitious, realistic, and sustained over time. Without such an approach, Europe risks becoming an increasingly aging, less dynamic continent, less capable of sustaining its own social model. And, to speak of the “topic of the day,” one increasingly incapable of maintaining an ambitious geopolitical agenda.