For many years, discussions have revolved around Europe’s demographic crisis in its various forms. At Rethink, we observed a worsening trend in key demographic indicators as early as the end of 2022. Today, all European countries have fertility rates below the generational replacement level: each new generation is smaller than the previous ones. Moreover, most countries now record more deaths than births, with the “echo” effect of high birth rates from the 1960s-70s disappearing in all but a few. Added to this is the persistent issue of integrating migrants from outside the European Union, who generally have low employment rates and whose children perform relatively poorly in education. In fact, even aside from immigrant children’s school performance, there is a noticeable decline in the quality of pre-university education across much of Europe. PISA test results indicate a growing (negative) gap between Europe and East Asia. The result is problematic, as relatively skilled generations retire, and their role in the economy is taken over by smaller and often less qualified cohorts.

After many years of a gradually deepening demographic crisis, the situation has worsened suddenly in recent years. Several Central and Eastern European states have been particularly affected. Poland and Hungary, which pioneered well-funded pro-natalist measures, are among the countries where birth numbers have collapsed. In Poland, births have declined every year since the recent peak in 2017. By 2024, the number of births had dropped to just 252,000, a 35% decline in just eight years. This decline is particularly surprising given that, in recent years, Poland has attracted a significant number of immigrants and Polish citizens from the diaspora. Some of the countries affected by this accelerated demographic decline have already reached a point where the demographic crisis threatens their viability as nation-states.

The Baltic States and the “Depopulation Crescent”

The Baltic states have been particularly affected by the recent acceleration of demographic decline. Latvia, for example, recorded fewer than 12,600 births in 2024, a 43% decrease in just eight years. This figure is lower than the number of births among the Romanian diaspora in England, for example, and is dwarfed by birth totals registered in many cities.

Furthermore, the number of deaths climbed to over 26,300—more than double the number of births. The population decline is extremely rapid and continues an accelerated downward trend. In 1990, Latvia had almost 2.67 million inhabitants; today, it has only 1.85 million. In 1897, it had over 1.9 million. Essentially, Latvia’s population has returned to 19th-century levels. Moreover, the proportion of ethnic Latvians is lower today due to Soviet deportations and colonization after World War II. Nearly half of the current population is concentrated in Riga and its surroundings, while the rest of the country has just 15 inhabitants per square kilometer. This proportion is rapidly decreasing, making much of Latvia resemble the vast prairies of the American West more than other European countries.

Similar sharp declines have been observed in Lithuania and Estonia. In Lithuania, births have dropped by nearly 41% since 2015, while Estonia has seen a 33% decline since 2018. Like Latvia, Lithuania has recorded more than twice as many deaths as births.

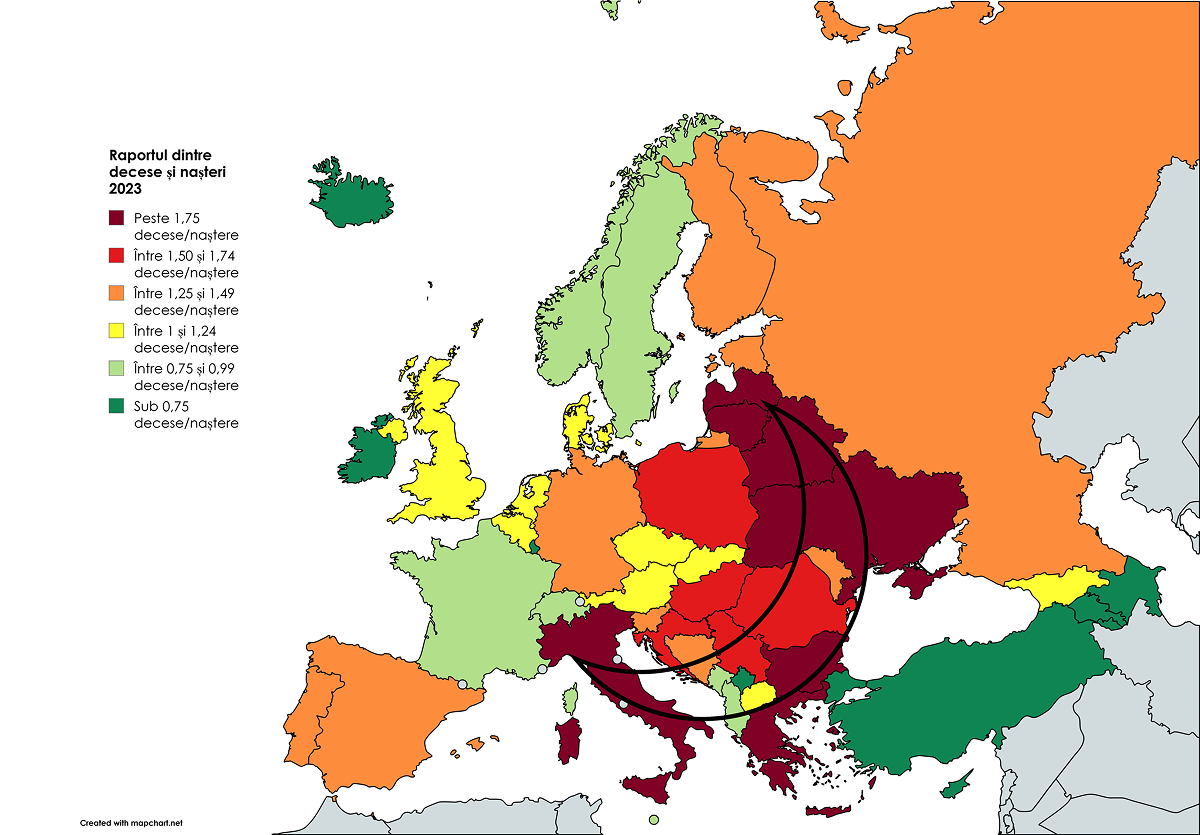

However, the Baltic states are far from alone in this situation. In 2023 (the last year for which we have complete data), several European countries—especially in the eastern and southern regions of the continent—recorded more than 1.75 deaths per birth. These countries form a “crescent” of accelerated demographic decline. The infertile crescent, if you will.

The Situation in Romania

Like Poland or Lithuania, Romania’s overall demographic situation has improved in recent years, mainly due to a recovery in migration balance. The country has become a destination for international labor migration, attracting people from Nepal, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Vietnam, and other countries. At the same time, the wave of emigration to Western Europe seems to have halted since 2019, as economic disparities between Romania and key emigration destinations have narrowed.

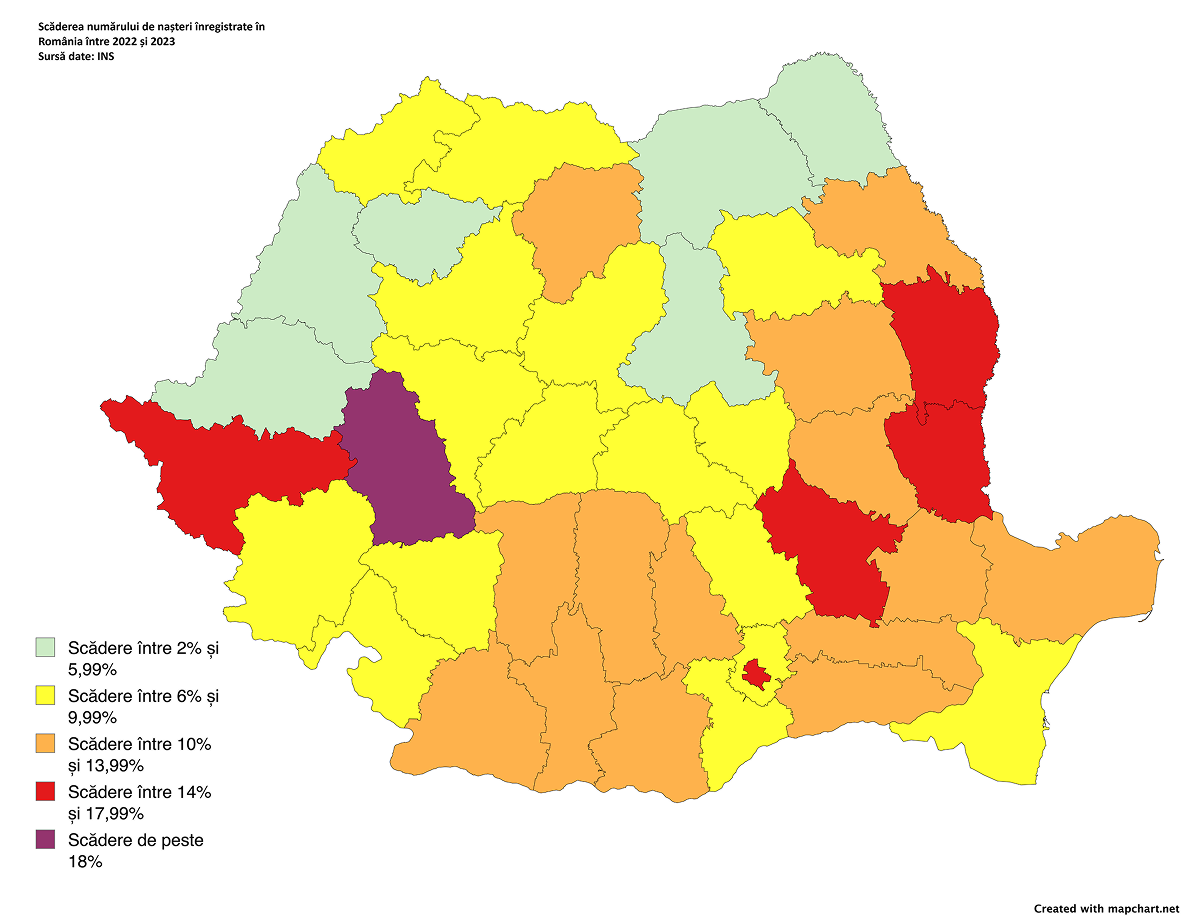

However, in a pattern again seen in Poland and Lithuania, domestic demographic issues have worsened. Notably, the number of births within the country has significantly declined. In 2023, the figure dropped to just 160,000. And the number seems closer to reality than previous reports issued by Romanian statistics. Rethink has previously highlighted the artificial inflation of birth statistics, where births among non-residents were included in Romania’s official numbers. There were blatant cases in Vaslui or Vârful Câmpului (Botoșani County). It appears that this issue was reduced in 2023, with the National Institute of Statistics (INS) reporting only about 5,000 more births than preliminary estimates.

Even so, many counties recorded sharp declines in birth rates. One example is Hunedoara, where a roughly 20% drop compared to 2022 accelerated the county’s population decline. Virtually every region in Romania experienced a steep decline in births in 2023. With just a few exceptions (e.g., Suceava), Romanian counties tend to have birth rates below 10 per 1,000 and fertility rates that signal a prolonged decline in births. A small number of localities still have high birth rates, usually those with very young populations (often suburbs), large Roma populations (e.g., Slobozia Bradului, Vrancea), or large religious populations (e.g., Vicovu de Sus or Cajvana, Suceava).

The Limits of Public Policies

Unfortunately, public policies attempted by various states to combat demographic problems have so far failed to yield the desired results. Hungary, for example, allocates a significant portion of its GDP to supporting families through subsidized mortgage loans, family car purchase assistance, tax deductions, and early retirement eligibility for mothers. Some of these benefits are available only to married couples, leading many to formalize pre-existing relationships. However, despite these measures, no baby boom has followed, although Hungary’s fertility rate is now above the EU average—something that was not the case before.

Similarly, several countries have attempted to open their labour markets to non-EU workers. These measures have also failed to have the intended impact, as there remains a significant employment gap between local-born populations (or EU immigrants) and non-EU immigrants. Employment rates among women from outside Europe remain notably low. Countries like Denmark and the Netherlands have produced reports highlighting the negative fiscal contributions of many migrant groups. Furthermore, a new challenge in attracting skilled immigrants is the declining fertility in the countries of origin themselves. Notably, the countries with the best education systems (and therefore the most qualified migrants) are often those experiencing the sharpest fertility declines.

One solution likely to become more prominent in mitigating the effects of demographic decline is the use of new technologies to boost productivity among a shrinking workforce and automate certain activities. But this too, is not without its issues. Some EU countries are heavily reliant on raxing labour for their fiscal sustainability, and will likely need to tweak the way they fund themselves.

And of what has been tried

Before jumping to the conclusion that “it can’t be done,” it is important to note that the pro-natalist policies adopted so far have not exhibited any notable radicalism, despite the existential nature of the demographic problem. One example is the unbalanced distribution of funding between pensions and family support. The financing consensus for dependents, settled in favor of pensioners, was normalized in its current form before World War I. Germany, the first state to systematize the idea of a pension for those finishing their working lives, did so at the end of the 19th century. At that time, high birth rates and low life expectancy meant that pensioners made up only a tiny fraction of the total population. The largest share of the dependent population consisted of children, many of whom entered the workforce before reaching adulthood.

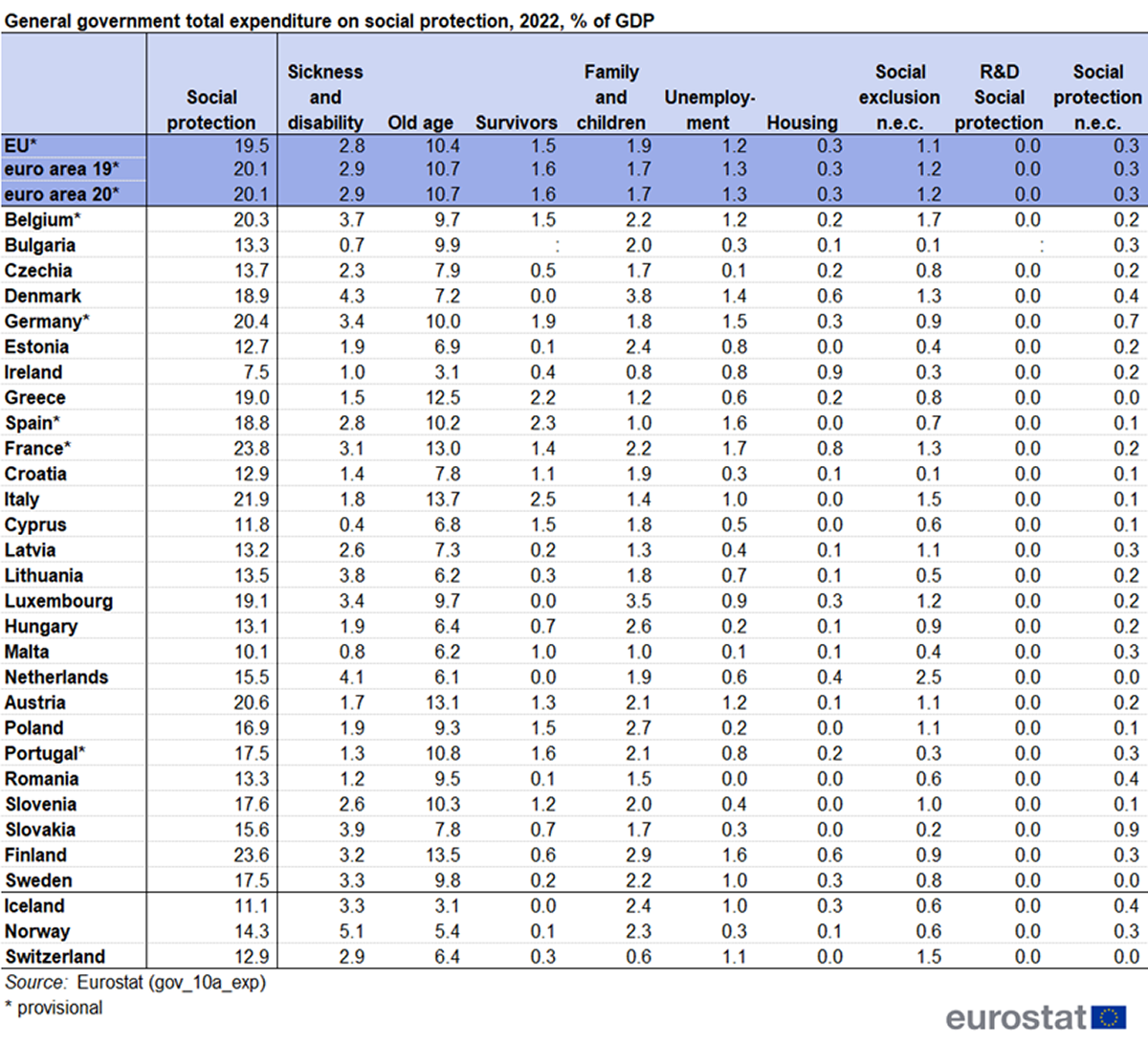

Today, the age pyramid has reversed, and the majority of the dependent population now consists of pensioners. These individuals generally receive state support not only for access to public services but also to cover their living costs. In contrast, the living costs of children are typically covered by their parents, with relatively limited child benefits or tax deductions available to families. In the EU, an average of more than six times as much is spent on old-age and survivor pensions as on family support. In countries like Spain or Italy, the ratio exceeds 10:1, with significantly higher poverty rates among children than among the elderly. Spain has also rejected pension reform altogether, as political parties prefer to court the votes of an aging population—even at the cost of mortgaging the country’s future.

Simultaneously, we are witnessing a systematic failure of housing policy. The age at which young people manage to acquire their own home is high across much of Europe, and social policies (such as the creation of social housing networks) do not benefit middle-class young people. Moreover, housing prices have risen dramatically in many European countries, a particularly acute problem in major cities. Last but not least, universal access to public nurseries is not guaranteed in most of Europe.

One area where some European countries have piloted substantial reforms is migration policy. Denmark, for example, is a notable case of a state that has dramatically restructured its criteria for access to temporary and permanent residence, citizenship, and family reunification to favour an increase in the proportion of highly skilled individuals among immigrants. Other countries have also introduced similar reform programmes, at various stages of debate or even implementation. As these reforms take time to prove their worth, we cannot fully gauge their eventual impact yet.

Demography as a Security Issue

Recently, there has been discussion about exempting EU member states from the Stability and Growth Pact’s deficit limits when it comes to defence spending. The pact was designed to prevent fiscal crises, but today, most European leaders view a potential security crisis as a greater threat.

Unfortunately, because the demographic crisis is difficult to solve—reliant on factors beyond direct government control (culture, global trends, demographic echoes of past dynamics)—and politically sensitive, it has largely been ignored. In Rethink’s view, this crisis weakens European states in general and the EU in particular. Under these circumstances, we believe that measures similar to the fiscal “bazooka” dedicated to defence should also be used to at least mitigate the effects of Europe’s rapid population aging and decline.

From our perspective, action is needed on two fronts. First, real investments must be made to combat the demographic crisis. Including demographic policies under the umbrella of security investments that qualify for exemptions from the Stability Pact’s rules would be a good step. Second, given that only a few demographic policies have shown success so far, the generalization of best practices and impact assessments is crucial. The time to act has already passed, and it is absurd for each country to repeat the same failed policies tried elsewhere.

Moreover, ideological obscurantism in addressing the demographic crisis must end. The issue is now so severe that only a combination of pro-natalist policies, immigration policy reforms, housing access measures, and investments in education and technology can prevent it from becoming a permanent crisis that erodes Europe’s future. Sure, for some groups, even talking about pro-natalism is uncomfortable ideologically or discursively. But if you are a right-winger who wants a minimal state, you still need a healthy demographic context to allow a private economy to flourish. And if you are a left-winger who cherishes the welfare state, acknowledging that rapid ageing is a big threat to it should be a very obvious conclusion.