Bucharest is by far the largest city in Romania, concentrating about 2.2 million inhabitants in its urban area, according to the 2021/2022 census. It is nearly six times larger than any other urban concentration in the country. Although its relatively peripheral position has allowed the emergence of other development poles in more distant regions (for example Cluj, Timișoara, or Iași), the capital’s gravitational pull is rapidly transforming the landscape of southern Romania: a large and dense metropolis surrounded by increasingly depopulated plains. This phenomenon is not unique to Romania’s capital—many dominant cities tend to empty out their geographic proximity, with the exception of their immediate suburbs and exurbs.

The 2021/22 census captured the phenomenon of population concentration in the Bucharest metropolitan area. All counties in the historical regions of Wallachia and Oltenia experienced population declines above the national average, with the exception of Ilfov county. The main counties of prior residence for Bucharest inhabitants included Teleorman (50,389 residents), Călărași (34,940), Ialomița (32,732), and Giurgiu (32,588) – all situated in the South of the country. Other counties from which people settled in Bucharest include Argeș, Buzău, Dâmbovița, Ilfov, and Prahova, each contributing over 25,000 residents. In contrast, more than 140,000 people moved from Bucharest to Ilfov, and tens of thousands more relocated directly to Bucharest’s suburbs from other counties.

From many points of view, the concentration of population in Bucharest is advantageous for Romania’s economic development as well as for the living conditions of those who make the move to the capital. People who live here have better job opportunities, can work in more productive industries, and their children can attend better schools. A concentrated and relatively affluent population generates a better supply of both public and private services. There are more types of schools, more kinds of shops and restaurants, and even more international flight connections.

However, in recent years, the rapid decline in fertility across most of Europe, Asia, and the Americas has led to a rethinking of the impact of cities on national demographics, beyond their role as magnets for internal migration and their capacity to enhance human capital. An emerging body of data and research indicates an association between urban densification and declining fertility. This trend appears to be consistent across multiple social, economic, and even cultural contexts. Rotella et al. (2021) observed a general association between decreasing fertility and increasing population density, present in most countries but moderated by social and religious norms. This seems to be backed by observational analysis of most metropolitan areas in Europe and the developed world. On the other hand, suburbs tend to exhibit higher fertility rates than metropolitan centres. Rodrigo-Camino et al. (2021) showed that suburbanization is strongly associated with increased fertility in Central and Eastern Europe and (to a lesser extent) in Southern Europe. This trend was not observed in the northwestern part of the continent, where the authors believe that migration toward metropolitan cores may explain the differing trend.

In recent years, some countries have seen a narrowing of the fertility gap between urban and rural areas, driven by a decline in rural fertility and in the number of children considered “ideal” in villages and small towns. This phenomenon was observed by Rieder et al. (2024) in Austria, but it exists in other countries too. For example, the recent sharp fertility decline in Poland appears to be “driven” by rural areas. Both cities and villages in Poland contribute to the overall demographic decline, with the highest fertility rates found in the suburbs and rural areas near Warsaw, Poznań, or Gdańsk. Yet even in countries that show this convergence trend, capital cities intramuros continue to have low fertility rates. For instance, Vienna has a TFR (total fertility rate) below the national average, despite the presence of a large number of non-EU immigrants who previously raised average fertility levels (Statistics Austria, 2024).

Focusing the analysis on Central and Eastern Europe, we can observe that all capital cities tend to have fertility rates below the national average—except in cases where they are grouped together with their surrounding suburbs.

Tabel 1 Fertility in cities and capitals in CEE. Source: Eurostat demo_r-find3. *The UTA NUTS3 regions for Bratislava and Belgrade also include most of their respective suburbs.

In nearly all cases where cities are analysed separately from their peripheral areas, suburban fertility was not only higher than that of the capital but even above the national average (as seen in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, or Hungary). In Bucharest, the pattern was reversed: residents of Ilfov county (statistically) had fewer children than those in Bucharest, with a fertility rate of just 1.20. This situation may partly be an artifact of data collection, such as an underestimation of Bucharest’s population (which would artificially inflate its TFR). Even so, the general trend of suburbs compensating for the low fertility of the metropolis appears less pronounced in the Bucharest–Ilfov area than in other European countries.

It is unlikely that overall density by itself has a direct suppressive effect on fertility. More likely, this effect is mediated by factors such as expensive and small housing, a lack of childcare infrastructure, social or economic costs stemming from the labour market structure, and mobility challenges for larger families.

Many of these factors are strongly present in Bucharest, though sometimes to a lesser extent than elsewhere in Europe. For example, housing prices have risen more moderately in Romania than in other European countries, although apartments and houses in Bucharest remain significantly more expensive than the national average.

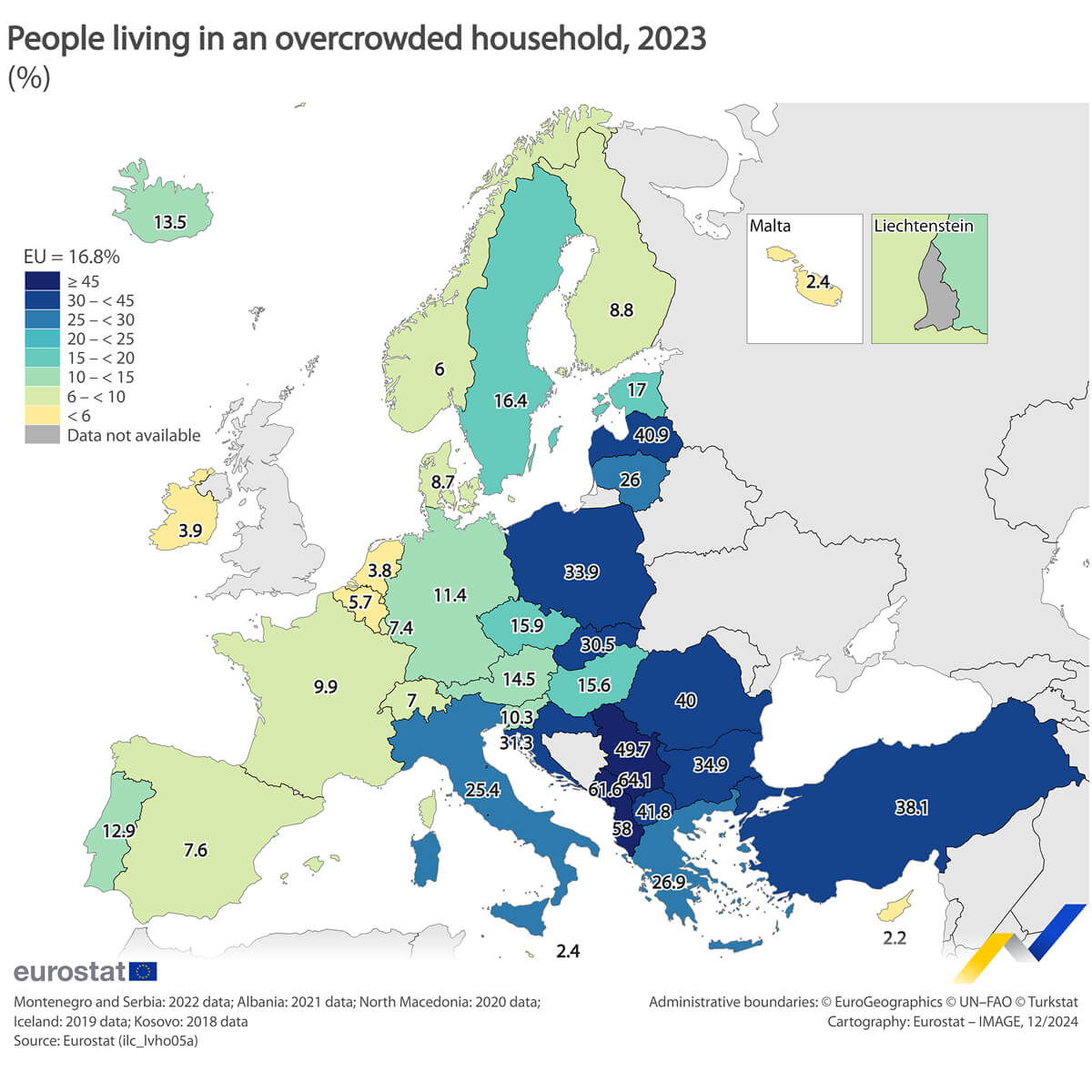

Romania has a high number of overcrowded dwellings. This issue is common across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).

Existing housing, on the other hand, is very small. For example, more than half of the apartments for sale in Bucharest have one or two rooms. A family with a 12-year-old child living in a two-room apartment is considered, according to Eurostat’s definition, to be living in an overcrowded dwelling. Given that studios and two-room apartments of 40–50 square meters are the norm in many neighbourhoods (including many new developments), the living space is often insufficient for families.

This context has fuelled the desire to escape to the suburbs. In Popești-Leordeni, Bragadiru, Tunari, Voluntari, or Domnești, tens of thousands of new homes have been built in the last two decades, often without coherent urban plans, without nearby schools or childcare facilities, and without functional public transport networks. Notably, Bucharest lacks a coherent suburban rail network segregated from road traffic, which makes these communities relatively isolated in terms of actual travel time to centres of interest within the city proper.

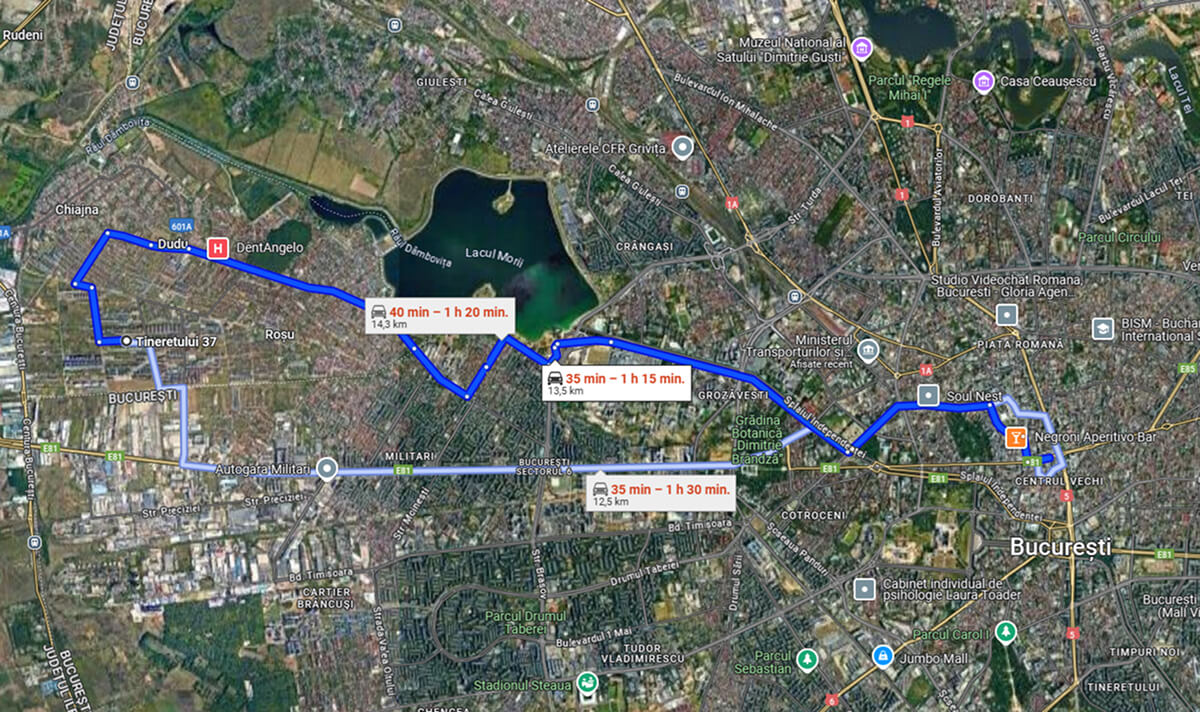

Moreover, the suburbs built in the immediate vicinity of the city were built with high densities, sometimes exceeding the average density of neighbourhoods inside the city. This is especially evident in Chiajna (“Militari Residence”) or Popești-Leordeni. Due to the lack of metro access, some of these neighbourhoods become isolated from the rest of the city during rush hours, forcing residents into very long commute times. These are often worsened by double-commutes, as many parents have to take their children to inner city schools before going to work.

Although located only 9–10 km from the city’s centre, the commute from the Militari Residence area in Chiajna to Piața Universității exceeds 75 minutes during rush hours. (Google Maps map.)

The suburbs contain the same small housing units found within the capital itself, with the main advantage being lower prices. On the other hand, since they offer neither space, nor nearby public services, nor easy mobility, they carry an increased risk of long-term ghettoization.

Fig 2. In contrast, from the Buftea train station area in Ilfov county, it is possible to reach the city center in under 40 minutes, thanks to the railway infrastructure and metro connection. Despite this, there are no real estate developments in this area.

In contrast, areas that are relatively well connected to the capital, such as Buftea, contain very few new developments. Buftea Station offers frequent and fast connections during peak hours (4 trains per hour, travel times under 20 minutes), yet the area around it has not attracted significant interest from developers or individual builders. Physical proximity to the capital seems to take precedence in the decision to develop new residential complexes, even in the absence of adequate local services and non-road transport links to points of interest in the city.

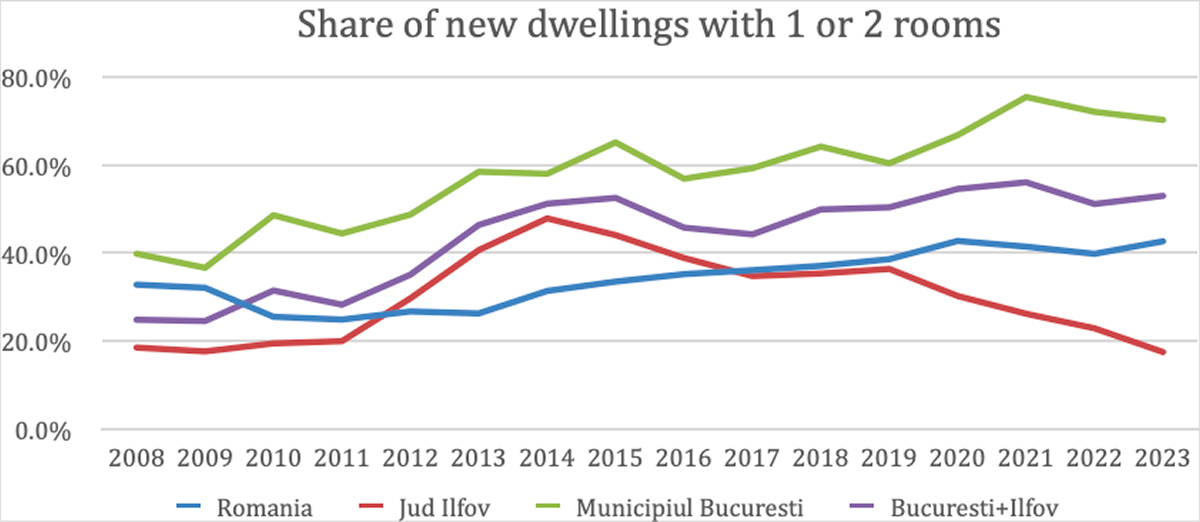

The lack of accessible suburbs exacerbates the problem of limited housing options for families. The proportion of small and very small dwellings has exploded since the financial crisis. In just the last 10 years for which final data is available (2014–2023), 51.4% of all homes built in the Bucharest-Ilfov area had only one or two rooms, making them unsuitable for the needs of families with children. In recent years, their share has exceeded 70% in Bucharest but has decreased in Ilfov, in a sign that the high-density low-quality developments in the immediate proximity of the city are beginning to fizzle out.

A mix of poorly designed policies, such as the differentiated threshold in the “New Home” program, along with buyer attitudes, has led to a market dominated by much smaller homes than in the rest of Europe or other developed countries.

Why is it a public policy problem?

Against the backdrop of an accelerating population decline and aging, the status of major cities as demographic traps represents a serious issue. Even a small variation in fertility can have problematic long-term consequences. And even though we do not yet fully understand all the factors contributing to the accelerating decline in fertility over the past decade (various emerging hypothesis exist, from smartphone use to ideological divergence between men and women), it is important that our urban planning policies do not become yet another factor worsening the demographic crisis at the macro level.

Romania is already burdened with many inherited or recently aggravated problems. Small housing units and mobility issues in the Bucharest metropolitan area (and other big cities) are among the most evident. Addressing these, as well as designing future urban planning policies that aim to build family-friendly cities, is essential to prevent the capital from becoming a driver of depopulation.

A demographic perspective is necessary when discussing urban planning practices and policies. Some of the popular ideas in urban planning—such as encouraging densification or prioritizing collective housing (often smaller) over single-family homes—carry the risk of exacerbating certain demographic trends. The efficiency generated by dense housing (lower infrastructure costs, easier service provision, more environmentally friendly cities) can come at the expense of exacerbating the existing demographic crisis. Density can become a trap—especially when applied without spatial consideration or social empathy. Furthermore, there is no absolute in terms of what the proper density of a city is. Budapest, although much less dense than Bucharest (even when considering just its built-up areas), has a higher share of public transport users. It is not suffocating, but it is dense enough to provide viable mobility solutions for its population via its trains, suburban trains, metro, trams and buses. Pro-density movements that have emerged in reaction to extreme sprawl in North America and parts of Europe should be critically analyzed through the lens of their impact on local demographics—especially in the case of Bucharest, a city that is fairly dense even by European standards.

At the same time, a number of shortcomings absent in other European capitals should be addressed in Bucharest. Perhaps the most important is the lack of suburbs with their own public services and accessible by public transport. An additional priority for Bucharest’s Ilfov suburbs is the construction of schools, clinics, parks, community centers, and rail connections to the city center. Today, Bucharest is surrounded by a ring of bedroom suburbs, connected to the center only by roads, traffic jams, and frustration.

Designing an urban and suburban rail system

Most of the large cities in Europe tend to have both a suburban train system operating on the national railway network infrastructure and a metro system largely serving the inner city. There are, of course, exceptions. Some cities—especially those with limited suburbanization—rely exclusively on the metro. A good example would be Sofia, in Bulgaria. Other metropolitan areas—typically with lower density or more dispersed suburbs (such as Manchester, Birmingham, or Zurich)—tend to rely solely or mostly on suburban trains, without a complementary metro network.

Bucharest is among the cities that solely relies on the metro. In the future, it needs to take the mobility needs of its growing suburbs into account. The old metro network has relatively wide station spacing, enabling fast transit across the city. Extending these lines outward could effectively transform them into a solution for both urban and suburban transport. Some new lines, such as M5, would not be suitable as suburban transport solutions due to their short station spacing and longer transit times.

The CFR railway network serves multiple rural areas near the capital but suffers from the small number of key locations it connects within Bucharest. These include Gara de Nord or the Pipera-Petricani area near the northern business districts. However, it includes only two interchanges with the existing metro (Gara de Nord-Basarab and Republica). Under these conditions, creating a suburban train network centered on the CFR system would require better connectivity within the city itself.

Conclusions

In more and more countries, large cities are acting as accelerators of the trend toward aging and population decline, driven by decreasing fertility rates among residents. Suburbs, however, seem to compensate for the situation in metropolitan cores, mainly due to their more family-friendly housing options. This is the dominant trend in other countries in the region, including the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria.

Unfortunately, Ilfov lacks many of the ingredients that help families enjoy a high quality of life. There are few schools and clinics, few parks and community centres. In many cases, even spacious houses and apartments are lacking – although they are larger than those in Bucharest, one-third of the homes built in Ilfov over the past 10 years have only one or two rooms. Just over 40% have more than four rooms.

At the same time, modern mobility solutions that connect the suburbs to the capital’s centre and provide access to the benefits of proximity to a major European metropolis are missing. Bucharest-Ilfov is the largest urban agglomeration in the European Union without a suburban rail system, and the development of new housing is not aligned with the existing railway infrastructure.

References

Riederer, B., Setz, I. & Buber-Ennser, I. Urban-rural differences in the desired number of children in Austria 1986–2021. Österreich Z Soziol 49, 331–356 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-024-00578-y

Rodrigo-Comino, J., Egidi, G., Sateriano, A., Poponi, S., Mosconi, E. M., & Gimenez Morera, A. (2021). Suburban Fertility and Metropolitan Cycles: Insights from European Cities. Sustainability, 13(4), 2181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042181

Rotella A, Varnum MEW, Sng O, Grossmann I. Increasing population densities predict decreasing fertility rates over time: A 174-nation investigation. Am Psychol. 2021 Sep;76(6):933-946. doi: 10.1037/amp0000862. PMID: 34914431.

Statistics Austria. (2024, May 28). Population growth in Austria in 2023 considerably lower than in previous year [PDF]. Vienna: Statistics Austria. https://www.statistik.at/fileadmin/announcement/2024/05/20240528Demographie2023EN.pdf

Referințe 1. As per 2022 census data 2. In addition, many Western European cities have large shares of non-EU migrants (who tend to have high fertility rates) in some of their major cities 3. According to the imobiliare.ro website, query in May 2025 4. Note that in Romania a “two room” apartment is essentially a one bedroom apartment as per the definitions used in other countries, including a bedroom, living room, kitchen and bathroom with a mix of segregated and open floor plans. 5. Eurostat registered Romanian homes as by far the smallest in the EU in 2012. No other country had dwellings that were not, on average, at least 30% larger than those in Romania. 6. There are denser cities than Bucharest in Europe, mostly in the Mediterranean states.