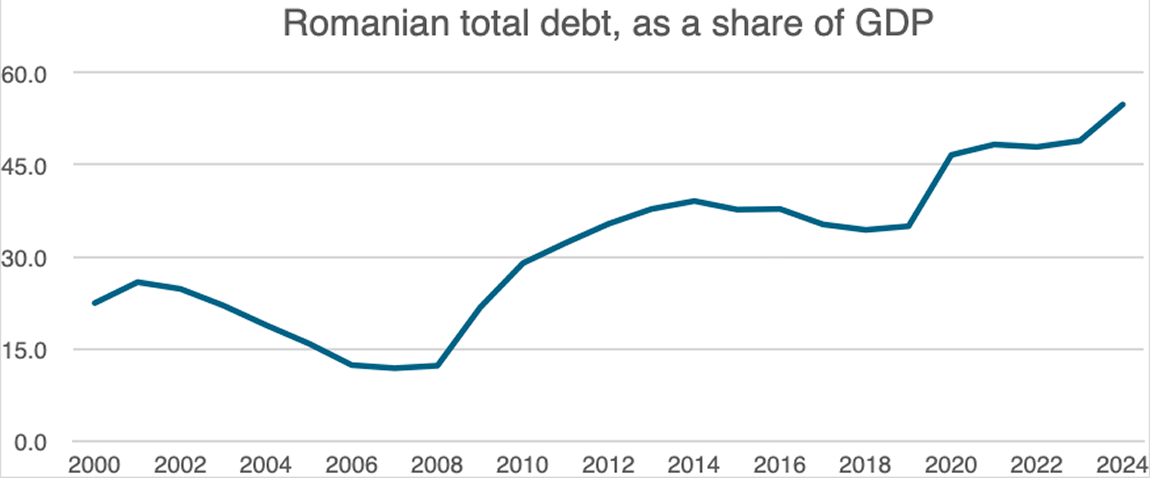

In the past 6 decades or so, Romania has been a notorious debtor, the kind that is lacking financial literacy and holding on to persistent bad habits. It borrowed heavily during the communist period to finance questionable projects, and later repaid those loans at the cost of a “lost decade,” through significant sacrifices by the population. Borrowing became necessary again after the Revolution. Romania has run budget deficits (spending more than it collects) every single year since the beginning of this century. In some years, such as 2020, the deficit reached 9.2%. In others, like 2015, it was as low as -0.5%. Even so, total debt has remained below the European Union average.

The reason is simple: economic growth has regularly supported debt repayment and reduced the impact of both domestic and external borrowing. With the help of loans, European funds, and remittances, Romania has developed a relatively modern and complex economy. It also benefited from a favorable international environment. As borrowing costs fell, the government could — in some years — refinance “expensive” debt by issuing new, “cheaper” bonds.

Thus, between 2001–2007 and again from 2014–2018, Romania actually saw sustained reductions in consolidated public debt, despite continuing to run annual deficits. Unfortunately for Romania, the years of relatively cheap borrowing following the 2008 crisis were followed by post-pandemic inflation and the war in Ukraine. As interest rates and yields demanded by investors increased, economic growth slowed. In the past five years, public debt has surged by nearly 20 percentage points, while GDP has grown only moderately.

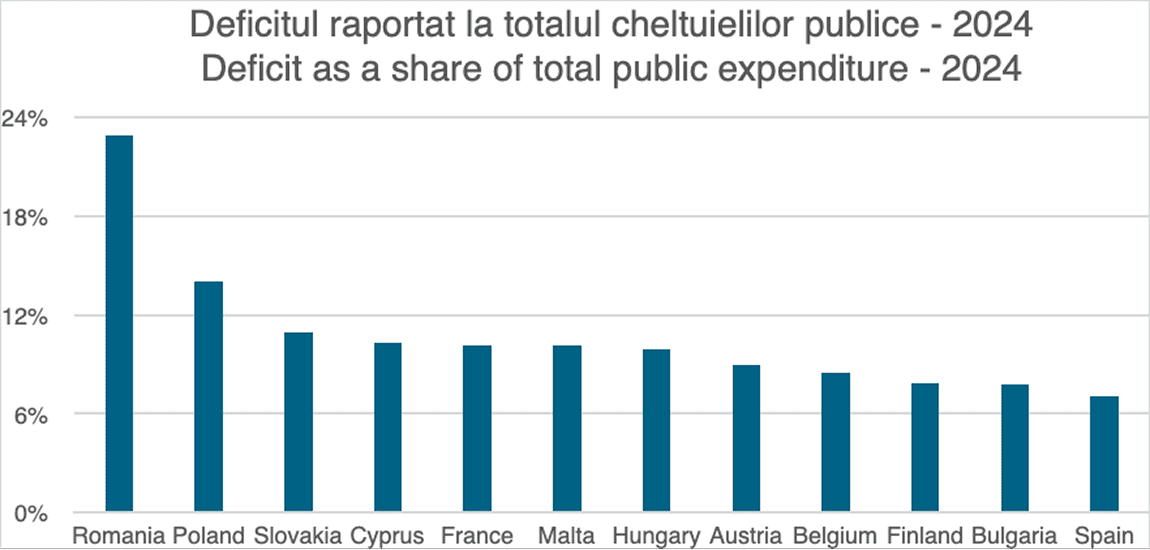

But the deficit-to-GDP ratio tells only part of the story. Romania’s public expenditures are relatively low in proportion to its own GDP. Under these conditions, the share of government spending financed by debt is by far the highest in the EU.

Figură 1 Deficit in relation to public expenditures. Data source: Eurostat

What does this mean in practice? First, it means that reducing the deficit requires a significant number of adjustments — and that the impact on citizens and businesses that depend on public financing in one form or another will be substantial. The problem is even more concerning because there are major obstacles to cutting certain categories of spending: quickly reducing special pensions, for instance, faces legal challenges; cutting health spending is difficult because of fixed drug costs and staffing shortages; and so on.

Moreover, once fiscal consolidation begins, it tends to slow economic growth, making it necessary to tax the existing economy more aggressively. Low-margin businesses are particularly vulnerable and may be forced into restructuring or closure. This can feed a sustained cycle of economic contraction, made worse by the absence of a medium- and long-term development strategy.

Living on debt can be expensive

There is another consequence: a high share of interest payments within the budget occupies future fiscal space. Every euro paid to creditors is a euro not available for public investment, education, or healthcare. Over time, a vicious cycle emerges: lower investment leads to weaker economic growth, reducing government revenues, pushing debt even higher and forcing the state to pay higher risk premiums — meaning more expensive borrowing.

In countries that already have high debt levels, interest-rate shocks hit the budget directly, making fiscal consolidation more painful and often pro-cyclical. This is why, when the 2008 crisis hit Europe, the strategy of the Baltic states (sharp and fast adjustments) proved more effective than the Mediterranean states’ attempt to “limit the impact.” Short-term pain was severe — major protests, tens of thousands of young people leaving, and brutal recessions (Estonia’s economy contracted -14.6% in 2009, compared to -4.1% in Greece). But in the mid-term, the Baltics recovered faster: Estonia exited the crisis by 2011, while Greece only recovered in real terms around 2016 and is still behind 2008 levels on some key indicators.

How much does Romania pay to service its debt?

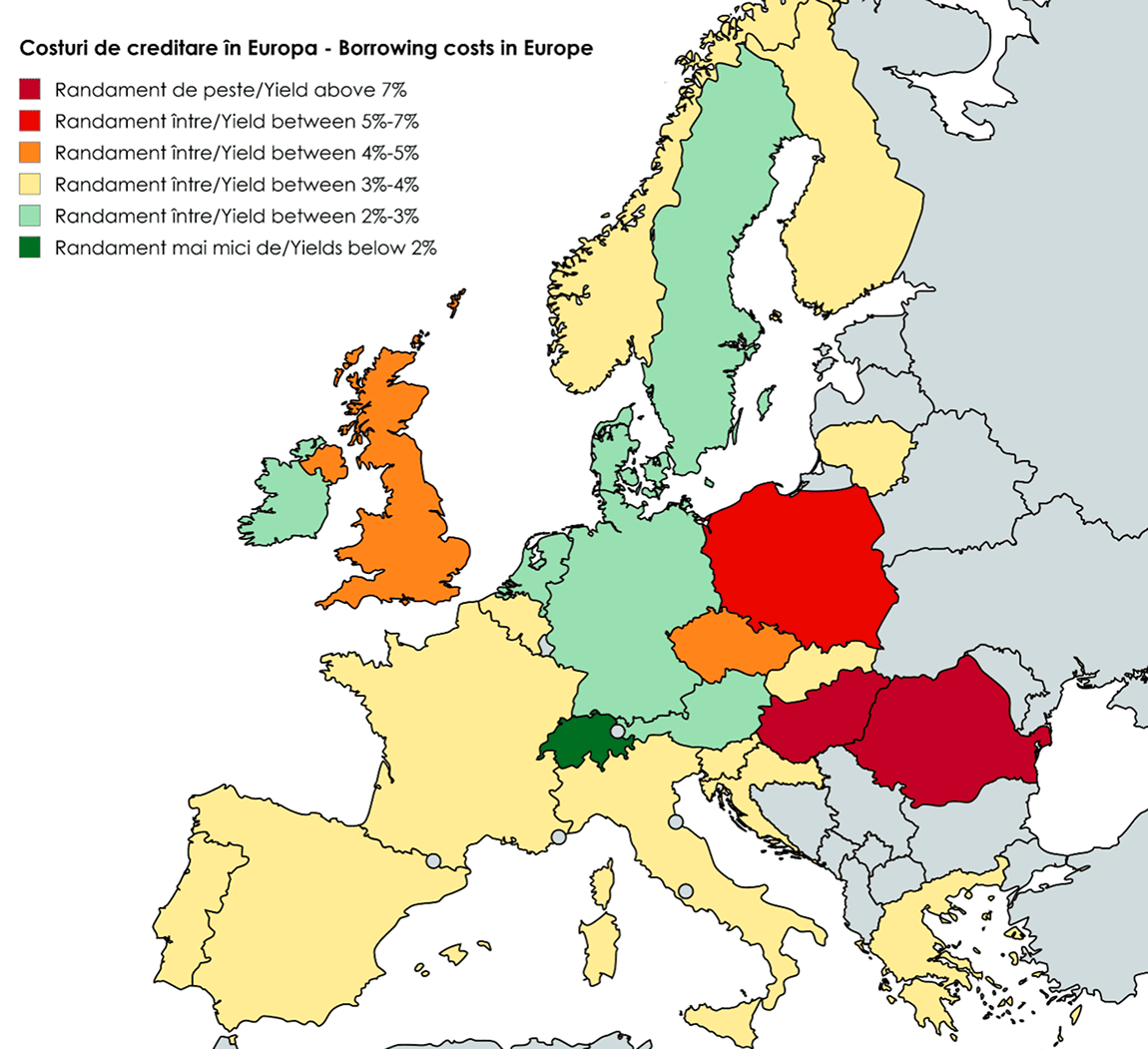

Romania currently faces very high borrowing costs — the highest in the European Union. Many factors contribute to this, but limited investor confidence plays a major role. Investors will accept lower yields on government bonds from “trustworthy” countries, but demand higher returns when lending to states like Russia, Turkey, Romania, or Hungary.

Yields represent the cost of borrowing for a state — and Romania’s 10-year government bonds now offer returns above 7%. Romania pays creditors more than 7% interest per year on these instruments, and those costs must be included in future budgets. The speed at which public expenditures are reduced will determine how large the debt-service burden becomes in the years ahead.

Romania is already paying significant sums for interest on public debt, and this burden has increased rapidly. Interest costs now exceed 2% of GDP — well above the European average — highlighting the growing pressure on public finances. But new borrowing is even more expensive: issuing new debt equivalent to 8% of GDP in 2025 would mean over 0.5% of GDP in annual interest payments in future years. In absolute terms, that means roughly €2 billion per year drained from future budgets. This is the cost of plugging our deficit for a single year.

Those billions cannot be invested — they shrink the fiscal room available to the government. They will be taken from education, health, major infrastructure projects. Combined with rising pension costs, the expensive debt is pushing Romania toward long-term impoverishment. Running large deficits is, in this sense, a harsh form of intergenerational injustice. Romania in 2023–2024 resembles a father who buys a TV on installment payments and then hands the bill to his child just starting out in life.

Future generations of Romanians will have far fewer tools to govern the country if too much public spending must go to servicing historical debt. And once the large baby boomer cohort retires, another major source of pressure on discretionary spending will arise.

There is growing political rhetoric today against spending cuts undertaken by the government. But cuts will happen regardless. Debt service is a priority expenditure that cannot be reduced without creditor consent. If the government won’t be imposing budget cuts, the cold, implacable math of debt and interest payments will.

A crisis of courage?

Cutting public spending almost always triggers protests and carries political risks that do not exist when deficits are created. This is why politicians and public officials often have no real incentive to think long-term or take responsibility.

Many cuts are truly painful and occur in critical areas, worsening already difficult situations in the short term. When the Baltic states abruptly reduced public spending in 2008–2009, they deepened their emigration problems. Key investments were delayed and social tensions erupted.

On the other hand, trying to reconcile the incompatible agendas of actors who want to maintain current spending (or rationalize it without affecting their own interests) can produce damage that persists much longer.

The crisis caused by excessive debt, costly borrowing, and declining investor confidence is not unique to Romania. Much of Europe — aging, resistant to reforming the welfare state — faces a similar challenge. France is a visible example: under the weight of a very generous pension system and amid strong resistance to reform from both the public and National Assembly, repeated government crises have erupted and investor confidence has eroded. Eventually, the French will also face a choice: cut social spending through political decision-making, or allow rising debt-service costs to shrink fiscal space until cuts become unavoidable.

The cold hard truth for Romania and Europe is that their ageing societies now deliver meager returns to most of their investments and pro-growth policies. As such, borrowing leads to less growth and is unlikely to be cushioned by a better, larger economy in the future. As such, Romania and Europe will be increasingly forced to live within their means or at least close to them.

Summary

- Romania is facing a crisis stemming from oversized public spending funded through domestic and external borrowing.

- Borrowing costs are high, and there is a serious risk of burdening future generations with interest payments.

- Although sharp spending cuts and tax increases can have significant short-term economic consequences, in the long run they free up billions of euros for essential projects — instead of servicing debt.

- Regardless of political decisions, the fate of Romania’s budget now lies largely in the hands of international markets. The government is obligated to prioritize debt service over other spending.

- The retirement of the 1967 baby boomer generation will further limit discretionary expenditure. By 2032, Romania must confront that moment with minimal debt burden.